Response to Final Reports from the Presidential Task Forces

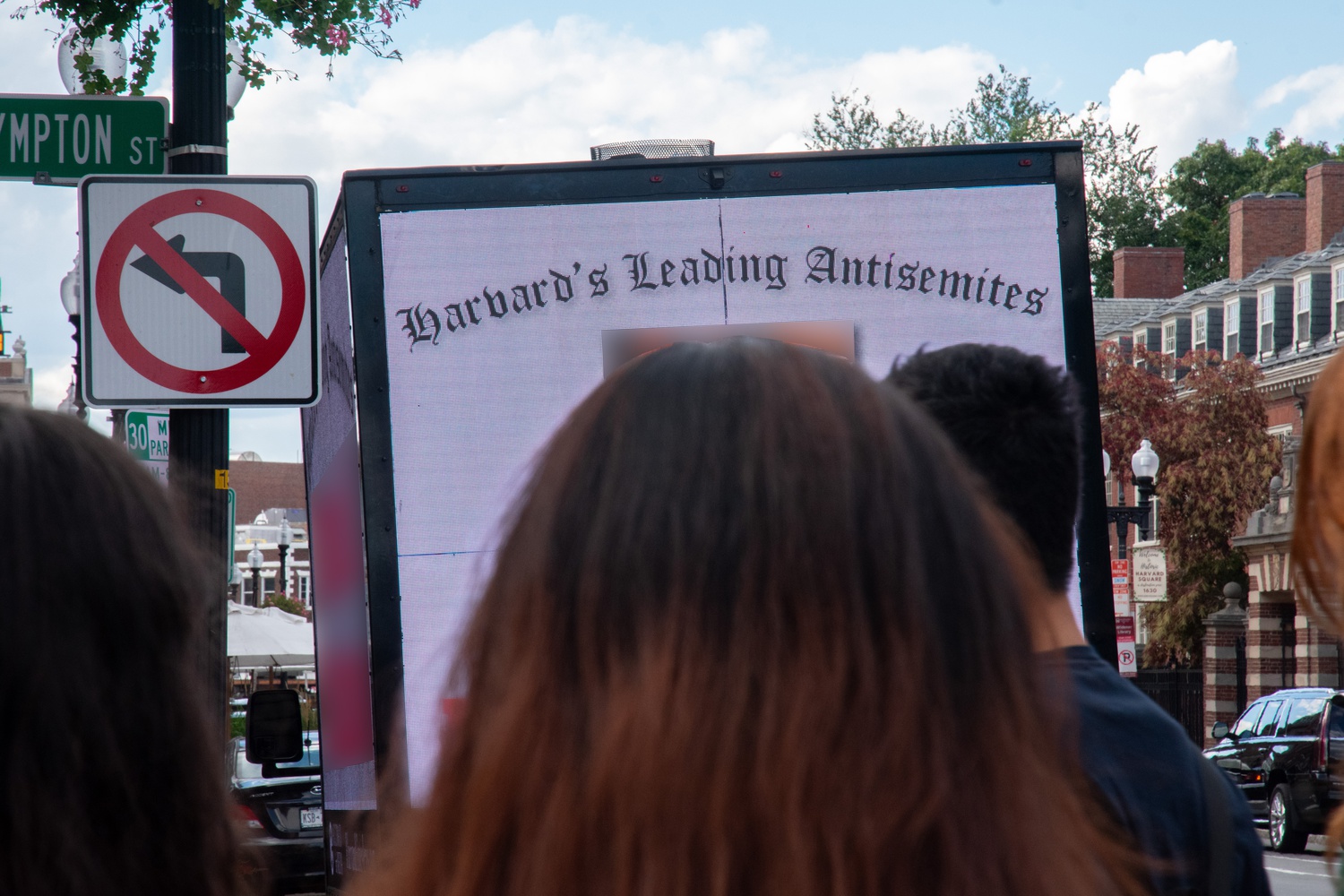

On April 29, amid pressure from the Trump administration to disclose alleged examples of campus antisemitism, Harvard finally released the final reports of the two anti-bias task forces it had commissioned 15 months prior: one from the Presidential Task Force on Combating Antisemitism and Anti-Israeli Bias, and one from the Presidential Task Force on Combating Anti-Muslim, Anti-Arab, and Anti-Palestinian Bias. Compared to the antisemitism report, the report on anti-Muslim bias is less thoroughly researched, and nearly a hundred pages shorter. At an event on campus, President Alan M. Garber ’76 referred to it in passing as “the other report.”

The formal differences between the reports reveal Harvard’s insidious dual interest: to erase Arab and Palestinian history and to disqualify any basis for the future study of Palestine.

The most damning example of Harvard’s selective and strategic erasure lay in the discrepancies between the reports’ sections intended to provide readers with historical context. The antisemitism report dedicates 90 pages to historical context, replete with anecdotes and external links regarding the history of “the Jewish Experience at Harvard up to October 7, 2023.” The corresponding section in the anti-Muslim report, entitled merely “Historical Context,” is just seven pages long, and skims over four centuries of history in two small paragraphs, citing Harvard’s “limited engagement” with Arab and Islamic history before the late 19th century as an excuse.

Who gets to have a history? Whose experiences on Harvard’s campus are protected? In the task force reports, the power of personal narrative is conferred only upon those students whose viewpoints agree a priori with the University’s. Whereas the stories of Jewish and Israeli students are carefully transcribed in a history section the length of a small novel, Muslim and Arab students’ experiences are numericized, summarized, and flattened into statistics.

Still, the numbers speak for themselves. According to the final reports, 56 percent of Muslim students reported feeling physically unsafe on campus, compared to 26 percent of Jewish students. About 92 percent of Muslim students reported fearing repercussions for sharing their opinions on campus, compared to 61 percent of Jewish students and 59 percent of all students. These data demonstrate the grave impacts of anti-Arab intimidation and Islamophobia at Harvard, compared with the heavily inflated and instrumentalized phenomenon of antisemitism.

In other areas, the antisemitism report claims but fails to sustain a standard of objectivity in its methodology. Despite a vow “to share what [they] were told generally without overlay or gloss,” the report’s authors express their personal biases in prose that is by turns overly sentimental and overtly racist. Throughout the antisemitism report, instances of even the most peaceful anti-Zionist speech are deemed automatically antisemitic and threatening, despite acknowledgments elsewhere in the text that the terms must not be conflated.

The recommendations of both task forces, unsurprisingly, are toothless and bureaucratic. Endorsements of respectful disagreement and a “pluralistic” campus environment abound, such that the very word “pluralism” — just as we have seen with “antisemitism” — begins to lose its meaning. The reports claim to strive toward the image of Harvard as a site of friendly, vigorous, and unrestricted ideological exchange. What they markedly overlook is the University’s rampant suppression of pro-Palestine speech — including the gutting of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, or the cutting of ties to Birzeit University in the West Bank — that foreclosed the possibility of academic freedom from the very beginning.

A glaring contradiction in the recommendation sections of the reports only further proves Harvard’s utter disinterest in taking tangible action to promote belonging on campus, let alone divesting from Israel’s genocide. Despite the very clear call to establish a professorship and eventual chair of Palestine Studies in the anti-Muslim bias report, the corresponding section of the antisemitism report reads: “We must strive to avoid a situation [...] where ‘Palestine Studies’ becomes an instrument of faculty and student advocacy.” In other words, Harvard students should be the kind of people who can learn about a genocide and feel content not to act against it.

What the weak and occasionally contradictory recommendations of the task force reports show is that Harvard’s actions in the future will not be in response to the grievances of Harvard’s Muslim or even Jewish students, but in order to preserve its reputation among wealthier donors. Harvard has already sacrificed its own students and educators to this end. The anti-Muslim bias report’s explicit recommendation to preserve the CMES and strengthen the Religion and Public Life program at the Divinity School exemplifies this; the program was gutted before the reports were even released.

What the members of the antisemitism task force actually recommend is a permissive, non-disruptive attitude toward the Harvard-funded genocide of the Palestinian people, under threat of referral to the Administrative Board. They expect us — while our school and our government send missiles into hospitals, while they starve thousands of babies — to “demonstrate civility,” to “cherish the opportunity to learn with and from one another.” In the face of such cowardice, the student movement learns from the people of Palestine, who are teaching us how to dismantle the structures that keep us all unfree.