We Keep Us Safe When Harvard Won't

In a few months’ time, you and your peers will pack up and move to Harvard or another university of your choice. For all of us, the transition is complicated: we bring our bags and boxes along with a host of anxieties. We worry about finding our people, passing our classes, and adjusting to a strange, faraway place. And for those of us in vulnerable bodies, we pack another anxiety with us. Will we be safe from sexual violence in college?

More than half of sexual assaults on college campuses occur between August and November. In the first few months following move-in, especially as first-years, we shove ourselves into uncomfortable social situations in order to meet new people. In the back of our heads, we grapple with the mounting anxiety that we will become that statistic — that we will be harassed, groped, or raped, and our experience as students and humans will be indelibly marred.

As women, femmes, and trans and nonbinary people, the numbers are not on our side, and here at Harvard, neither is the administration. Less than three months after arriving at Harvard, I was sexually assaulted by another first-year in a public venue, where several other bystanders witnessed him assault two other first-year students as well. Like all other first-years at Harvard, I had completed the mandatory sexual assault training modules, so with the support of others by my side, I did what the University told me to do: I initiated a Title IX complaint.

Like so many other survivors of sexual assault at Harvard, I wanted some semblance of restorative justice. Instead, I left with the sense that Harvard had punished me for demanding accountability. For more than a year, my complaint was booted around by Harvard’s Title IX committee, the Office for Gender Equity, and third-party legal representation. I was trapped in a cycle of endless, hours-long Zoom calls with lawyers where I was forced to restate evidence I had already produced months prior and was faced with repeated iterations of the same questions, each essentially amounting to “Just how sure are you that you were sexually assaulted?” Harvard’s “painstaking, fact-finding mission” reached its lowest point when one of their lawyers asked me if I could hold my hand up to the Zoom screen and imitate what my assaulter’s hand looked like when he groped me.

The year I spent trapped in this cycle was supposed to determine if the perpetrator would face the Administrative Board, which adjudicates student disciplinary cases. But I had no faith that this day would come, nor that Harvard would yield a verdict that could justify the dozens more hours I would have to spend testifying in front of the Ad Board. Enraged at the University and ashamed for wasting my own time, I threw in the towel and ended the Title IX process myself.

This whole time, I knew that I was not alone, not least because I knew the two other students who suffered assaults by the same male student that night. By design, the federal Title IX process exists to isolate survivors by preventing them from filing joint complaints against a shared perpetrator. But if anything, it was a comfort to know that the others, though they did not want to file their own complaints, wholeheartedly supported me every step of the way.

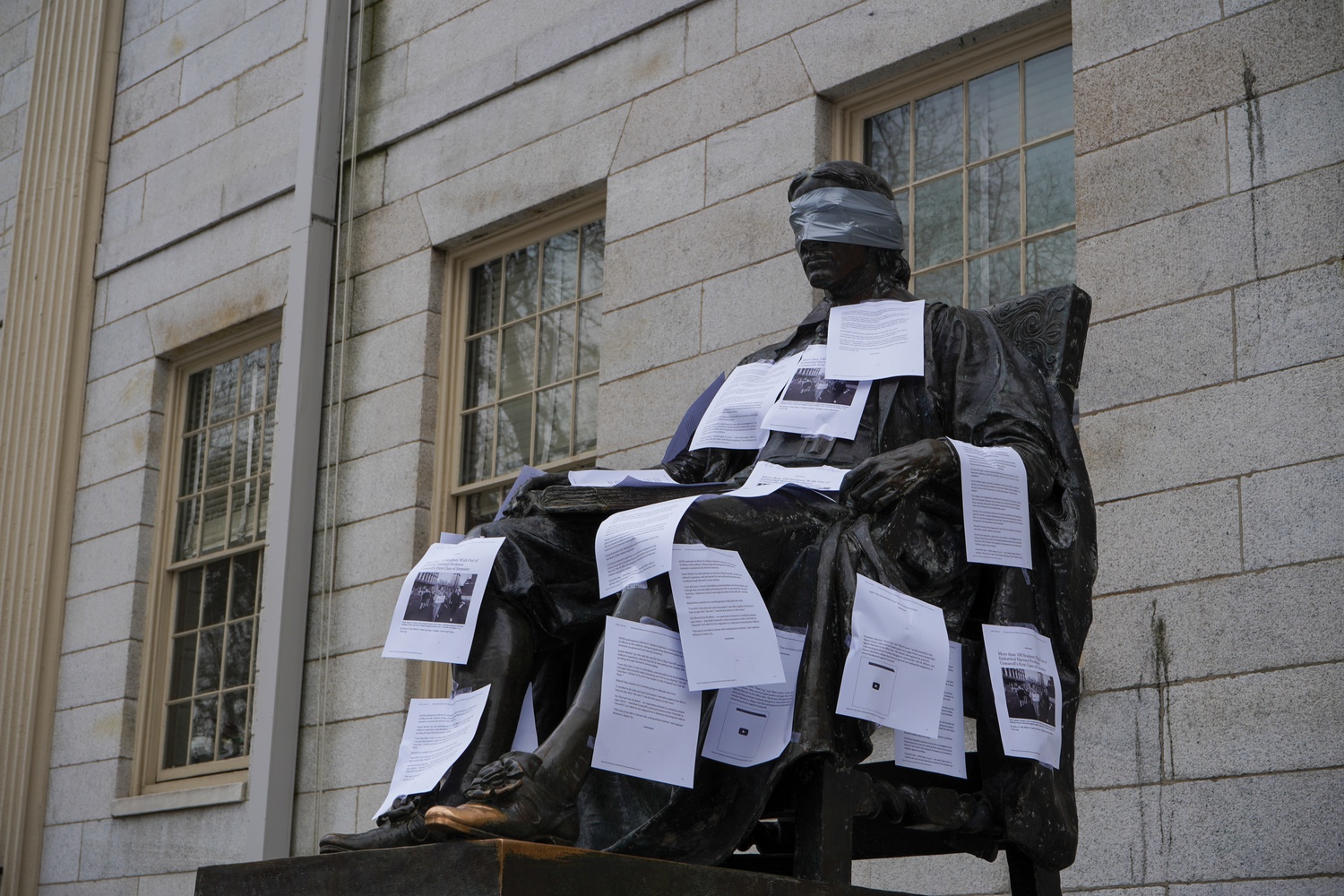

Not even a semester after I ended the Title IX proceedings, I was one of over 30 students disciplined by the Ad Board in for my alleged “participation” in Harvard Out of Occupied Palestine’s encampment, which stood for twenty days to demand that Harvard disclose and divest from its investments in Israel’s genocide of Palestinians. Instead of engaging with these demands, Harvard expedited its disciplinary procedures to punish pro-Palestine speech, in a way it had never done in response to past student movements.

For many student protestors, the only “evidence” the University brought against us was the allegation that we had “participated” in the encampment over a random smattering of dates, and a single image: a sign hanging from the gates forbidding “erecting structures” like tents. Whereas its investigation of my sexual assault dragged out for more than a year, Harvard snapped to action to punish me and other student protestors within mere days, completely ignoring the “due process” the University swears it cares so much about.

Campus safety is and has always been a political issue. When Harvard’s own students and workers come forward against the perpetrators — of sexual harassment and assault, racism, ableism, gender-based discrimination, and other forms of harm — we become the problem. We are the threat to Harvard’s image, to the prestige of their tenured white male professors, and the profit they reap from rapey rich kids whose parents donate buildings.

Over the last two years, Harvard sat idly by as its own students’ faces and names were plastered on doxxing trucks that drove around Harvard Square. Harvard said nothing about “civil discourse” as a professor’s wife tailed two students wearing keffiyehs and hurled racist insults at them. Harvard said nothing about “campus safety” when its own students faced violent threats online, or were harassed by counterprotestors, or when a former Israeli prime minister “joked,” at a talk at the Business School, that all pro-Palestine student protestors should be handed exploding pagers.

Harvard’s attacks on pro-Palestine speech, action, and academic programming reveal that Harvard is more than willing to put its own students in harm’s way, if it believes doing so will protect its image. All the while, as the University offers unequivocal support for a genocide that has murdered more than 60,000 Palestinians to date.

We are faced with the bitter lesson that Harvard’s administration does not care about a single one of us. No matter how much you love the institution, it will never love you back. But we never learn this bitter lesson alone. Instead, it is fuel for our solidarity and our organizing — if the University will not keep us safe, then we will.