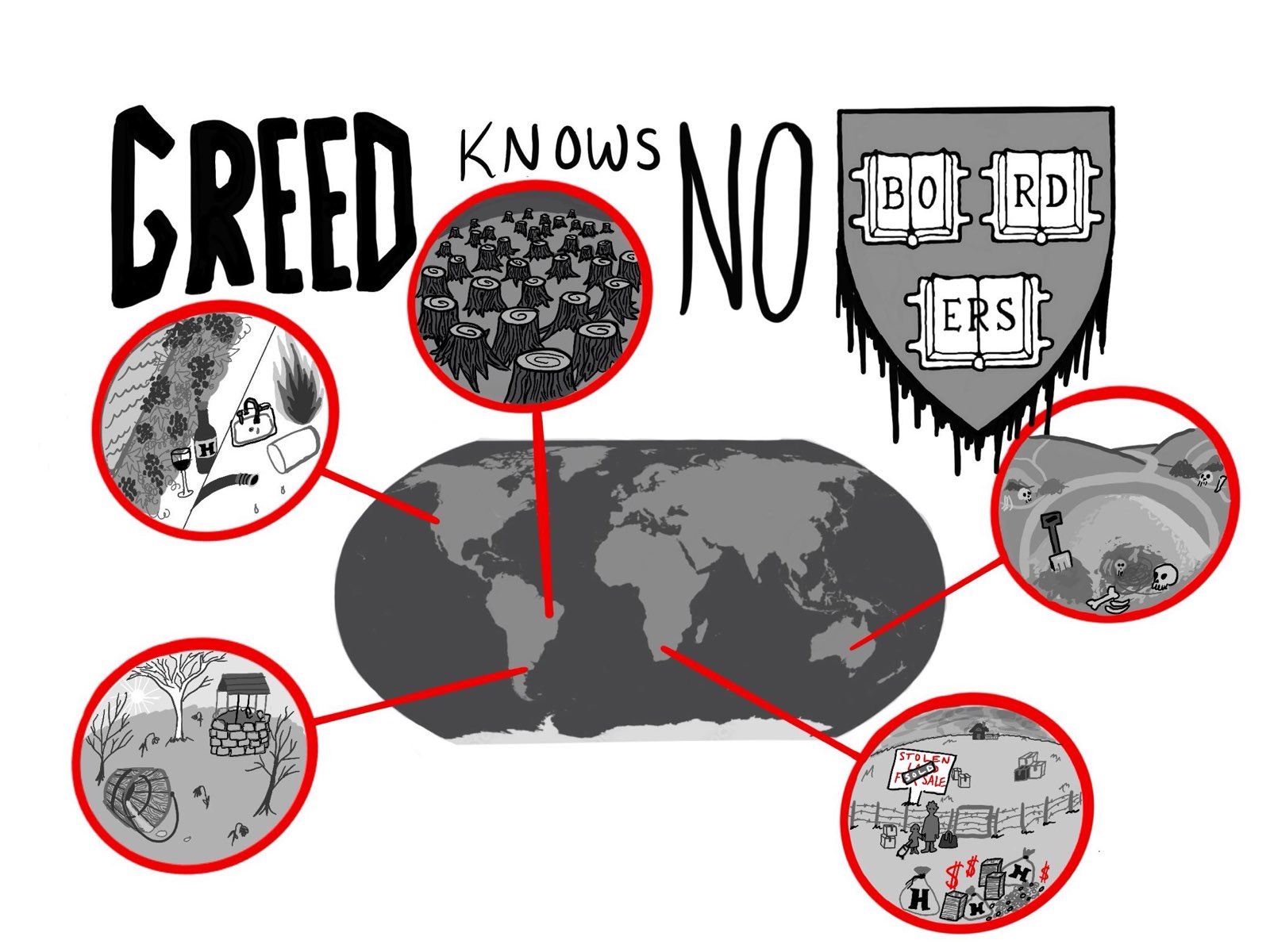

From Cerrado, Brazil to Cuyama, California

Harvard’s dirty investments and global land grabs

If the Harvard Management Company is managing anything, it is the University’s complicity — in the form of a $53.2 billion endowment. Day in and day out, HMC works to shield Harvard’s investments from public scrutiny, especially its land holdings.

In recent years, HMC has acquired and commodified land all over the world in pursuit of endless profit. As of 2018, the University had invested nearly $1 billion in buying up farmland around the world. As one of the world’s largest investors in farmland, Harvard’s massive, far-reaching agribusiness model infiltrates local farming communities and drains the environmental resources they rely upon.

Harvard’s known acquisitions span the United States, Brazil, Uruguay, Romania, Russia, Ukraine, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. Much of the investment structure is shrouded in secondary companies, subsidiaries in Delaware or the Cayman Islands with hard-to-trace names. These land acquisitions have provoked land conflict, polluted with industrial-grade fertilizers, robbed communities of their livelihoods, and killed local farmers and their families.

Harvard’s holdings are concentrated in Brazil, specifically the Cerrado region, which holds five percent of the world’s biodiversity. In recent years, Harvard has deforested Cerrado and significantly expanded plantation agriculture, driving the destruction of Brazil’s vital natural regions. On top of ecological concerns, no matter what Harvard may pretend, land is never conveniently empty. Cerrado is home to nearly 80 Indigenous ethnic groups who have no protection against corporate land grabbing.

The Granflor group, a Brazilian business partner of a Harvard-owned subsidiary, illegally and violently displaced local families from public land. According to a Brazilian court in October 2020, Harvard and TIAA, a pension manager utilized by Harvard, illegally acquired around 500,000 acres of Brazilian public land. These two investors are the largest foreign buyers of farmland in the country, and they have deforested thousands of hectares. The people in the Cerrado have no food security; many are forced to emigrate to escape starvation, or to attempt to work at company farms which instead puts them in debt.

Harvard’s reach has caused land conflict and dispossession around the world. Between 2008 and 2016, Harvard transferred over $70 million to a South African subsidiary, Russell Stone, to acquire farm properties in the country, working against local post-apartheid fights to redistribute farmland to dispossessed Black workers. Managers of farms restricted the land use rights of families in the area, including rights for cattle to graze and for families to access burial sites. After public backlash, Harvard reportedly directed Russell Stone to sell farmland on which people were already living, but Harvard continues to manage large-scale farmlands in the country.

In Australia, the Aboriginal Land Council has accused Harvard of destroying and excavating Aboriginal cultural sites on property it is developing. Although the Harvard Management Company refuted these claims, independent organizations have found at least six Aboriginal occupational and burial mounds harmed in the process. Ninety percent of such Aboriginal mounds have been found to contain burial sites. In Argentina, Harvard’s timber plantations have made water inaccessible for residents, in a region where the lack of running water forces them to depend completely on groundwater. The mass deforestation associated with many of Harvard’s projects worldwide leaves residents unable to plant their own crops, instead forcing them to depend on an unstable employment cycle in which Harvard’s plantations hire seasonal workers.

Nearer to home, Harvard spent around $100 million throughout the 2010s buying up lands on California’s central coast, particularly in the Cuyama Valley, historically semi-arid rangeland. Harvard then planned a new vineyard, the largest in the valley, and built a wide irrigation system to serve it, drawing out groundwater from the already water-stressed region. The project has depleted groundwater basins in the region, and in 2023, after a Harvard subsidiary looked to install three large reservoirs for the vineyard, local farmers shared grievances with their county’s planning commission and eventually won out against the proposed developments. To this day, Harvard continues to invest in its vineyards, demonstrating a patent lack of concern for the region and its environment.

It is no coincidence that many of the communities most affected by Harvard’s agribusiness investments are Indigenous or otherwise marginalized. From Indigenous people in Brazil and Australia to farmworkers in South Africa, Harvard has shown that as long as doing so is profitable enough, it is more than willing to brutalize and dispossess those that have been rendered powerless by colonialism and capitalism. This ruthlessness extends, of course, to Palestine, as we have seen throughout Israel’s accelerated genocide in Gaza.

The demands for disclosure of Harvard’s endowment holdings include, among many other things, transparency around its agribusiness investments. These ventures are not exceptions, but rather a portion of a larger-scale investment strategy that sees global inequalities as opportunities for profit, undoubtedly impacting far more lives and communities than are presently known. The fight for Harvard’s divestment from Israel is intertwined with fights for land justice around the world.