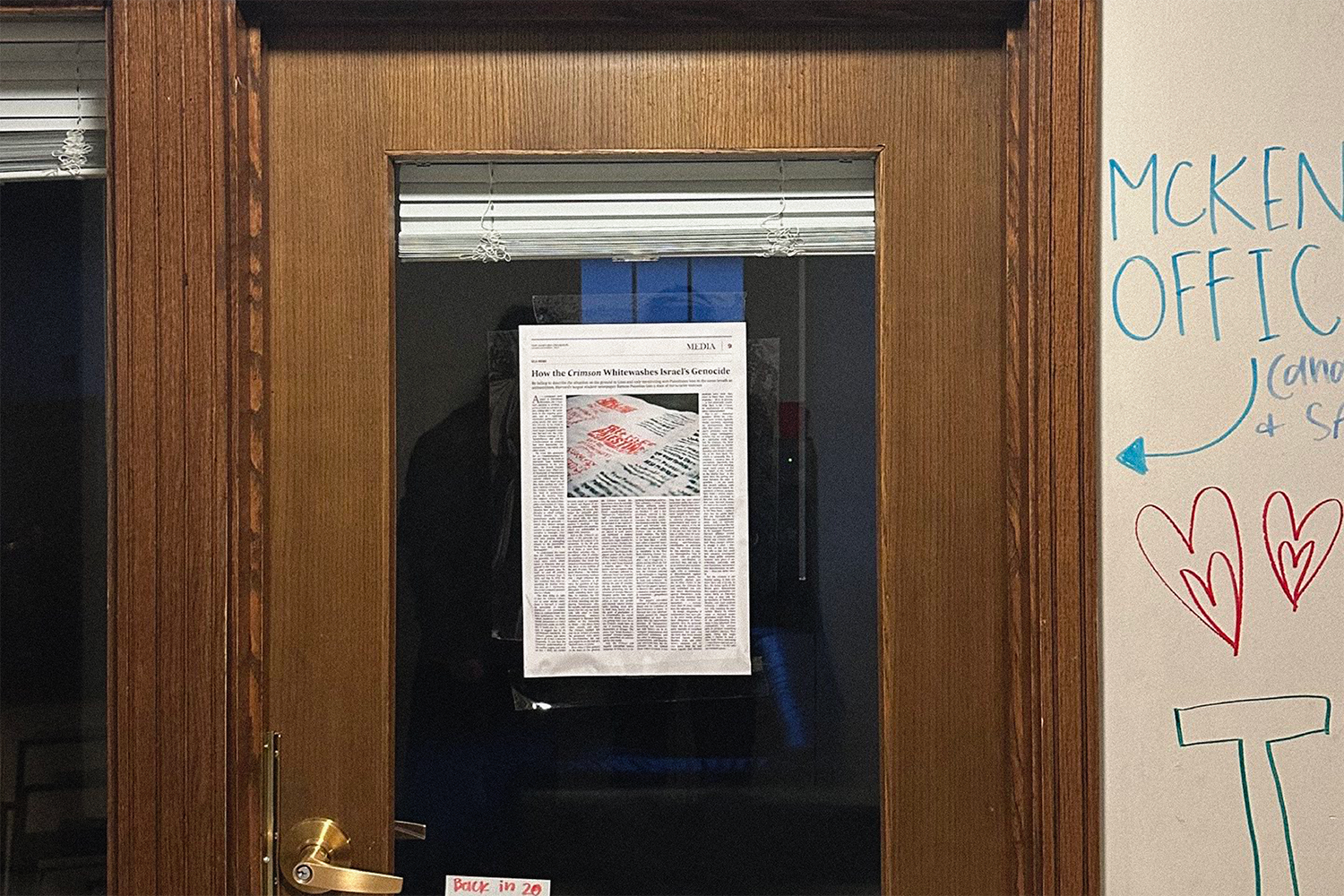

How the Crimson Whitewashes Israel’s Genocide

By failing to describe the situation on the ground in Gaza and only mentioning anti-Palestinian bias in the same breath as antisemitism, Harvard’s largest student newspaper flattens Palestine into a state of intractable violence.

As a newspaper dedicated to Palestinian liberation, the Crimeson’s purpose is twofold: to serve as both as a protest object, taking aim at the architects of the ongoing genocide, and as a legitimate alternative publication, covering stories that other outlets will not. As we wrote in our founding statement, our third target alongside Israel and Harvard was the Crimson, “whose coverage of the ‘Israel-Hamas war’ and its reverberations on campus has been inaccurate, unsympathetic, one-sided, and often racist.”

We wrote this statement for our Commencement issue last May on the heels of Harvard’s Gaza Solidarity Encampment. In the year since, the Israeli Occupation Forces have killed tens of thousands of Palestinians and maimed, displaced, and starved millions more. But you would not know any of this from reading our campus’s student newspaper. In the Crimson, which follows the lead of publications across the country, Palestine appears curiously frozen in time: the same Orientalist construction of a hazy, barbaric Middle East that Zionists have deployed for decades to rebuff critique. Twenty months in, and mainstream media would have it that the genocide — which they almost always call a war — is already too ancient to intervene in, too complex to untangle, even though more bombs drop with each passing minute and the job of untangling should be the journalists’. Why have they failed so thoroughly?

To understand the ways that the Crimson obscures the genocide, we reviewed every news article about Israel or Palestine that appeared in the Crimson over the past academic year. In total, we read 181 articles published between Sept. 3, 2024, and May 16, 2025. We feel confident that, even accounting for human error, this data set is representative of the Crimson’s journalism as a whole.

The first thing to note is that the Crimson claims not to cover stories unrelated to Harvard. It would be unrealistic to expect full-blown war journalism from an undergraduate student publication, even one whose masthead has direct family connections to every legacy news outlet on earth. But it would also be a mistake to suggest that by its self-imposed standards, the Crimson cannot talk about Gaza at all. In fact, it does so frequently. It’s just that the Crimson’s understanding of the conflict begins and ends on Oct. 7, 2023, the mythic terrorist attack in response to which any degree of annihilatory violence might be justifiable. Of course, the longer the genocide goes on — the more Palestinians that Israel kills, the more hospitals, shelters, and food sources it destroys — the less defensible this position, which was indefensible to begin with, becomes.

And so the Crimson’s account of the genocide cannot breach the subject of its escalation. Of the 181 articles reviewed for this piece, 70 of them, or more than one-third, mention Oct. 7. In contrast, only 25 articles say anything at all about the devastation that Israel has visited on Palestinians every day since, to say nothing of the past 76 years. This temporal fixation — the flattening of accelerating violence into a single infamous day — allows reporters to divorce the question of “supporting” Palestine from any discussion of the events actually unfolding there. Last May, for instance, the IOF launched a ground invasion of Rafah, bombing and displacing Palestinians who, for months, had been told by Israel that the city was their only “safe zone” in Gaza. Simultaneously, students encamped in Harvard Yard calling on the University to divest — but divest from what, exactly, and why? The Crimson couldn’t tell you: In its version of events, the protestors were merely “pro-Palestine,” the way you might be on the side of a football team, or peace.

[FOR TECH EDITORS: PLEASE EMBED THIS PDF HERE]

Even when it does gesture at the facts on the ground, the Crimson creates distance from them by carefully choosing which facts to substantiate. Operation Al-Aqsa Flood — usually described as “Hamas’s Oct. 7 attacks on Israel” — is frequently the only event canonical enough to be narrated in the reporter’s own voice. Subsequent developments in the genocide are placed in scare quotes and attributed to student activists, whose assessment of the facts might feasibly be clouded by bias. During a law school protest last semester, for instance, the Crimson reported that “participants displayed posters on the backs of their laptops with messages like ‘Israel is burning people alive’ and ‘Israel bombed a hospital, again.’” The reporters did not explain what these messages referred to. Although Israel has bombed hospitals and burned people alive over and over and over during the past 20 months, the law students were specifically protesting the destruction of Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital earlier that week: an attack on a tent camp that killed at least four people and severely injured dozens more, burning them alive in their tents. Surely one of the goals of journalism is to contextualize the events you write about; but someone getting their news from the Crimson would have no way of knowing about the destruction of Al-Aqsa. The claim that “Israel bombed a hospital” remains conspicuously unverified, an exercise left for the reader.

Still, the Crimson will happily regurgitate violent language as long as it is describing Palestinian actions. This semester, it wrote that “Hamas militants massacred more than 260 Israelis on October 7,” and it has previously referred to the day as a “terrorist attack.” Compare the moral conviction behind words like “massacre” and “terrorist” with the watery equivocation the Crimson uses to describe Israeli violence. The IOF’s air strikes and ground raids in the West Bank — which have killed at least 911 Palestinians since the start of the genocide — are downplayed as “instability in the West Bank following Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack.” In October 2024, after a day of staggering violence during which the IOF killed at least 56 people in Gaza and 36 more in Lebanon, the Crimson referred to the onslaught as “ongoing geopolitical developments in Gaza and Lebanon.” So demure! It must have been a relief for the paper’s lawyers to discover that, rather than a massacre, Israel had merely committed a geopolitical development.

The paper’s one-sided coverage of violence abroad bleeds into its treatment of discrimination at home. At Harvard last year, administrators punted the alleged harassment of their students into the labyrinthian recesses of bureaucracy, launching two simultaneous task forces: one to investigate antisemitism and anti-Israel sentiment, and the other to investigate anti-Palestinian, anti-Muslim, and anti-Arab bias. But the Crimson has not treated these topics as equal. It has long been the case across American media that coverage of pro-Palestinian viewpoints must be intercepted by an acknowledgment that some people believe such viewpoints to be antisemitic, whereas allegations of antisemitism may stand on their own. Indeed, of the 99 Crimson articles published in the last year that refer to bias of either kind, 89 mention antisemitism by name, and 66 do so without mentioning anti-Palestinian, anti-Muslim, or anti-Arab bias. The Crimson devotes far less attention to campus Islamophobia: Only 35 articles refer to anti-Palestinian, anti-Muslim, or anti-Arab bias, and only 10 do so without also mentioning antisemitism; of these, eight refer to institutional discrimination against pro-Palestine speech, not necessarily against people. In other words, in the past year, the Crimson has only published two articles about discrimination against Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim students that do not also mention antisemitism — a number more than 30 times smaller than the opposite case.

By design, allegations of antisemitism have been given far more media airtime than allegations of Islamophobia since the genocide began. But the most prominent example of racialized harassment last year was the truck that drove around Harvard Square doxxing Muslim, Arab, and other brown students; and we now know from the task force reports that Muslim students were more than twice as likely than Jewish students — 56 to 26 percent — to feel physically unsafe. Why, then, is the Crimson so uninterested in writing about Islamophobia?

This is not a rhetorical question. While the Crimson’s news section typically works reactively, reporting on developments shortly after they occur, it also regularly publishes news features, longer investigatory articles that are not pegged to a particular event. Last fall, for instance, the News board published an investigation into Harvard’s relationship with Birzeit University in the West Bank. The article is, unusually, fine. It employs a vacuous idea of journalistic objectivity that satisfies itself with devoting equal word counts to the two “sides” of the “conflict in the Middle East.” At the same time, the jarring contrast between the sides in question — on one hand, that Israel’s military raids and the constant violent detainment of Birzeit students have made it almost impossible for the university to function, and on the other, that some Harvard Zionists are mad at the results of student government elections in the West Bank — make it clear that the public backlash over Harvard’s ties to Birzeit was a manufactured panic. Still, it certainly seems to be the case that the investigation was prompted by the backlash: Prominent Harvard affiliates leveled charges of antisemitism at Birzeit, and Crimson editors took these charges seriously enough to pitch a closer look. At the very least, this tells us that they could have similarly investigated the many public accounts students have given of anti-Muslim, anti-Arab, and anti-Palestinian harassment and discrimination on campus — they just didn’t want to.

But the Crimson is not beyond saving, at least not more than any of us are. In fact, the better parts of the Birzeit piece demonstrate that student journalists can report fairly on Palestine, so long as they take the perspectives of Palestinian, Muslim, and Arab students seriously. A different Crimson, fully wielding the journalistic liberty its writers enjoy as Harvard undergraduates, might break free of the self-defeating fixations it has inherited from mainstream U.S. newspapers to produce something real, incisive, and true. Then again, doing this might make it harder to land a New York Times internship — even if your dad can put in a call for you — so the odds are anyone’s guess.